The Lertap5.xlsm worksheets

Now it would be useful to have a brief browse of Lertap’s built-in worksheets. There are six of them.

The Comments sheet is the first sheet to show when the Lertap5.xlsm file is opened. It isn’t much, just a welcoming title page (see it here). If you’re connected to the internet, a click on the hyperlink shown on the Comments sheet will take you to Lertap’s home page, which may also be reached by having your Web browser go to www.lertap5.com/lertap/.

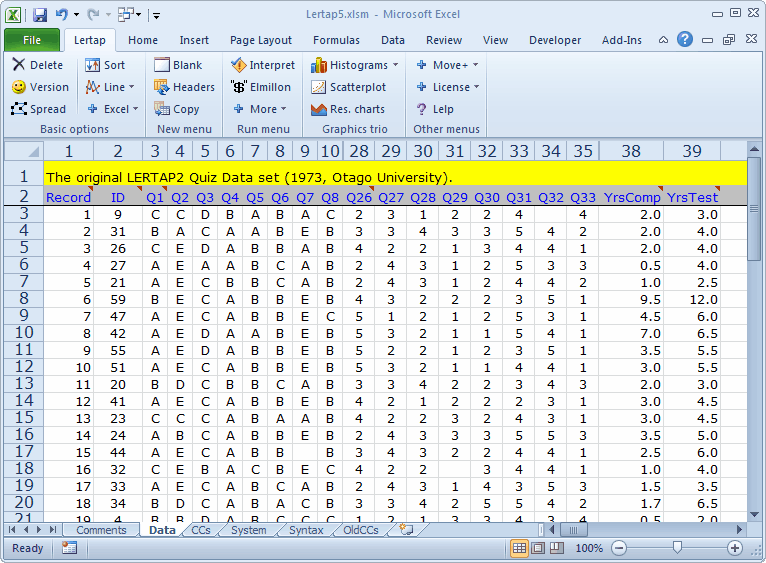

The Comments sheet may not amount to much, but the Data sheet, shown above, is packed with things to look at. It contains the responses of 60 people to 37 questions.

Of these, the first 25 questions have their responses recorded in columns 3 through 27 of the worksheet. The responses to these 25 questions, Q1 through Q25, consist of letters. These questions corresponded to a cognitive test designed to indicate how well the respondents had mastered an introductory workshop on the use of the first version of Lertap, a version which appeared in 1973. (In the snapshot above, only the first eight cognitive questions, Q1 through Q8, are showing.)

The second set of questions, Q26 through Q35, have their responses in columns 28 through 37 of the worksheet. These ten questions were affective in nature, asking respondents to report their attitudes towards using Lertap 2. A 5-point Likert scale was used to record answers.

The last two questions had to do with the number of years which respondents had been using computers and tests in their work.

How many rows are used by the Data worksheet? If you have opened the sheet on your own computer, you’ll find that 62 is the answer. The first row has a title, the second has headers for the data columns, and the remaining, beginning in row 3, have the answers given by the respondents, one row for each respondent.

Some of the cells in the worksheet seem to be empty. Cell R3C34 (row 3, column 34) for example, appears to have nothing in it. The respondent whose answers were recorded in row 3 of the Data worksheet did not answer Q32.

Note how we’re saying that these cells “seem” or “appear” to be empty. We say this as it’s possible there’s a space, or blank, recorded in the cell (in fact, we know this to be the case—unanswered questions were processed by typing a space, which Excel calls a blank). Blank cells are not empty, even though they certainly appear to be.

Before looking at the next sheet, CCs (for “Control Cards”), it will be worthwhile to summarise why we’d want to use Lertap to analyse the results seen in the Data worksheet. We could think of some “research questions” which we’d like to have answers to.

The results are from two tests, one cognitive, the other affective. We’d like to have a summary of response-, item-, and test-level data. We’d like to know, for example, how many people got each of the 25 cognitive items correct. Which of these items was the hardest for the 60 respondents? What did overall test scores look like? Do the tests appear to have adequate reliability?

The 10 affective items asked respondents to reveal how they felt about their introduction to Lertap 2. What was it they liked and disliked? How did their attitudes correspond to how well they did on the cognitive test?

We might also like to know how responses to the cognitive and affective questions may have related to the experience levels of the respondents. If they had been using computers for some time, were their attitudes towards the software more positive, or more negative?

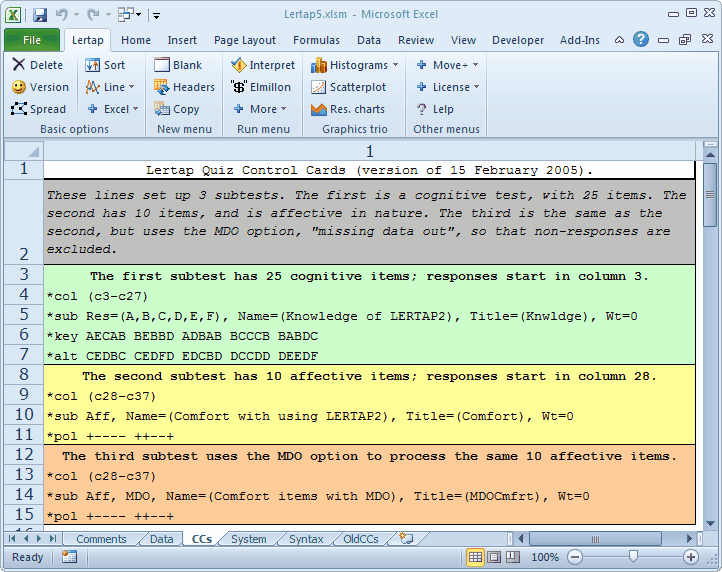

In order to have Lertap answer questions such as these, we first need to provide the system with what are referred to as job definition statements. This is done in the CCs worksheet. (Please see the Tidbits below. This particular CCs worksheet is somewhat complex, using lines and options which are by no means always required; for example, the *alt line is not often used; it's not common to have a workbook which has both cognitive and affective item responses.)

The CCs sheet shown above has 15 rows of information. Only rows which begin with an asterisk, * , are actually used by Lertap; the other rows are simply comments. In this example, rows 1, 2, 3, 8, and 12 are comments.

Rows 4 through 7 have to do with the first test, or “subtest”.

The *col (c3-c27) line tells Lertap where the responses to the subtest’s items are to be found in the Data worksheet.

The *sub card, with Res=(A,B,C,D,E,F), says that item responses were recorded as upper-case letters, A through F, and gives a name and title to this subtest. Titles are limited to eight characters in length.

The *key line gives the correct answer to each question, while the *alt card indicates that the items did not all use all of the response letters shown in the *sub card.

There are 25 entries on both the *key and *alt lines, corresponding to the 25 items on the subtest. The correct answer to the first item, or question, was A; this item used just the first 3 of the possible response letters, which would be A B C. The correct answer to the second item was E, and this item used the first 5 of the possible response letters, A B C D E. The actual items are seen below.

(1) |

Which of the following is not included in standard LERTAP output? |

|

A |

individual scores |

|

B |

subtest histograms |

|

C |

correlation among subtest and total test scores |

|

(2) |

What control word is used on which control card to activate the correction-for-chance scoring option? |

|

A |

MDO on *ALT |

|

B |

CFC on*TST |

|

C |

WT on*SUB |

|

D |

MDO on*FMT |

|

E |

CFC on *SUB |

|

The entries on the *key, *alt, and *pol lines have been grouped in sets of five, with a space between each set. It is not necessary to group by fives. The *key line, for example, could have been

*key AECABBEBBDADBABBCCCBBABDC

The *col (c28-c37) line in row 9 signals to Lertap that there’s another subtest to be processed. Answers to its items are found in columns 28 through 37 of the Data worksheet. The *sub card informs Lertap that this subtest is to be processed as an affective one (“Aff”). The last line, *pol, indicates that some of the questions were positive in nature, while others were negative.Two examples of affective items similar to those actually used are shown below; question (26) was a positive statement, while (27) was negative.

(26) |

Lertap seems powerful, but simple to use. |

|

1 |

strongly disagree |

|

2 |

disagree |

|

3 |

undecided |

|

4 |

agree |

|

5 |

strongly agree |

|

(27) |

The Lertap manual is lacking detail in many important areas. |

|

1 |

strongly disagree |

|

2 |

disagree |

|

3 |

undecided |

|

4 |

agree |

|

5 |

strongly agree |

|

In these little examples, note how the cognitive items, (1) and (2) above, use letters as response codes, while the affective items, (26) and (27) use digits. In current versions of Lertap 5, an item may use as many as 26 responses codes. Cognitive items do not have to use letters for their response codes—digits are fine. But, having said this, it is important to note that, unless you say otherwise by using Res= on a *sub line, Lertap assumes that cognitive items use A B C D as response codes, and that affective items use 1 2 3 4 5. These are the default Res= settings. In this example, an Res= declaration was required for the first subtest (a cognitive subtest), but not for the second and third subtests (affective subtests).

Finally, the *col (c28-c37) line in row 14 signals to Lertap that there’s a third subtest to be processed. In fact, this subtest consists of the same items found in the second subtest (row 14 is the same as row 9), but now the items are being scored in a different fashion, using the MDO option. Having items scored in different ways is not too uncommon; in mastery testing, for example, the same *col, *sub, and *key lines may be used repeatedly, with different Mastery= settings on the various *sub lines used to examine the effects of using different cutscores.

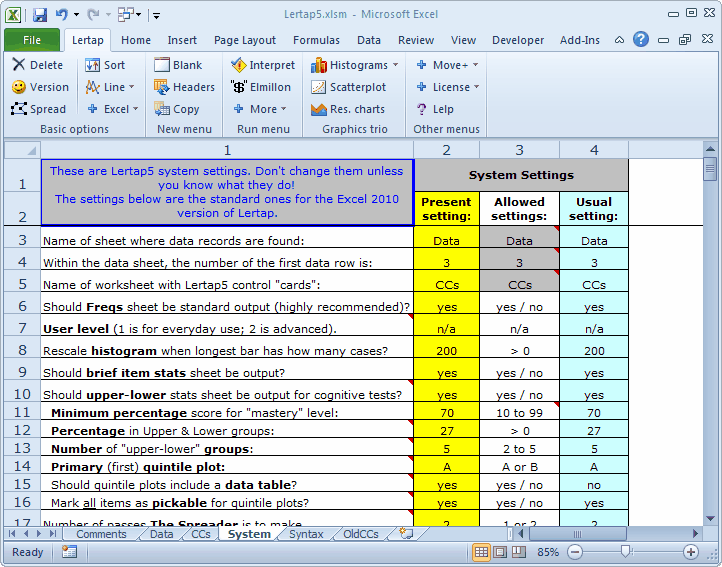

The System worksheet is where Lertap stores a variety of important settings. Much more about this worksheet may be found in another Lertap help file.

The fifth of the visible worksheets in the Lertap5.xls workbook is named Syntax. This sheet is used to provide examples of what job definition lines can look like; it’s meant to serve as a sort of on-line reference which may obviate the need to refer to this Guide.

Users may add their own examples to the Syntax worksheet. How to do this is discussed in Chapter 10, Computational Methods.

The last worksheet, OldCCs, may be useful to veteran Lertap 5 users, people who may have started to use Lertap 5 and its printed manual when it first appeared in the year 2001. At that time the CCs worksheet was a bit different to the one seen now.

Summary

The Lertap5.xlsm file is a workbook which contains six visible worksheets, and the collection of macros which effectively define the Lertap software system. The worksheets are named Comments, Data, CCs, System, Syntax, and OldCCs.

Of these, Comments and Syntax, are information sheets. The Data and CCs sheets, on the other hand, are much more substantial, content-wise. They exemplify what a dinkum Lertap Excel workbook looks like, and they are used as the main ingredients in the "Cook's tour".

Let’s gather some speed. Ready to see some action? Open the Lertap5.xlsm file on your computer, and read on. (Maybe get a fresh cup of coffee or tea first.)

Tidbits:

The CCs worksheet in the Lertap5.xlsm workbook is perhaps unnecessarily complex for beginning Lertap users. Much more elementary examples start here. The recommended reference for boning up on CCs worksheets and their control lines is the on-line help system.